One of my favorite flute warmups is “Flexibility–I (after Sousseman)” from Trevor Wye’s Tone book. (Just buy the whole omnibus edition and thank me later.) This exercise is value-packed and meticulously thought out, and leads inevitably to some fundamental truths about flute playing.

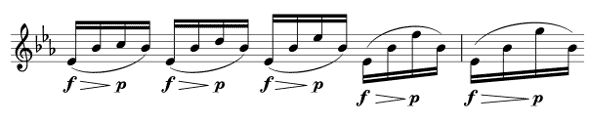

The exercise is slurred arpeggiated figures, like this:

As you might expect, the figure gradually expands to larger intervals and notes in the third octave. It’s challenging to make the intervals smooth and accurate, but especially so if your approach to flute tone production is based on unclear or faulty pedagogical concepts. Wye provides some very crucial advice that is key to getting the most out of the etude, and to developing a solid approach to tone production.

Wye suggests first playing the etude omitting the highest notes, and dynamically shaping the figures as follows:

The forte dynamic on the lowest notes demands a low, open voicing and strong breath support, feeding into an aperture that is “focused” (small). The dynamic shape, stretched mostly across a single note (B-flat here), also requires the aperture to be agile and flexible, opening slightly for the loudest notes and closing slightly as the volume decreases.

The next step is to “work up” to the high note, “so that it sounds softly, but not flat:”

There is a lot going on here. The aperture has to continue to move flexibly in order to produce the dynamic effect. Voicing has to be low and open to make the low notes full and responsive. Breath support has to remain powerful and steady to keep the pitch buoyed up. And something has to happen to produce the register change.

Many flute teachers suggest making the aperture smaller to achieve the higher registers, but this ties register to dynamics—the larger aperture makes the low notes loud, and the small aperture makes the high notes soft. Others suggest something like increasing air pressure or using “faster” air. This can be accomplished by increasing breath support and/or by using a higher voicing; changing these has a destabilizing and register-bound effect on pitch and tone. It also creates the opposite dynamic problem from aperture-based register changes: the higher notes are always loud, and the low notes are always soft.

The most effective approach is to allow the embouchure to push forward for notes in the upper registers, and to relax back for lower registers. This allows breath support, voicing, and aperture to function separately, and intonation, tone, and dynamics to be manipulated independently. The Wye exercise demands all of this from the flutist.

This is a great exercise to incorporate into a daily warmup. I especially like it for its coverage of several flute tone production concepts, since doubling on several instruments means I don’t have as much time to devote to the flute as I would like. Work on it slowly and deliberately—as Mr. Wye points out, “this may take time.”

I spotted this new review of Chris Vadala’s

I spotted this new review of Chris Vadala’s